Brad's Ultimate New York Yankees Website

Explore the rich history of the New York Yankees, from their humble beginnings to their record-breaking achievements. Discover fascinating stories, legendary players, and unforgettable moments that have shaped the Bronx Bombers into the most successful franchise in sports history. Go Yankees in 2024!

John Sterling! You will be missed! Thanks for the memories!

About Ultimate Yankees

Discover the rich history of the New York Yankees with Ultimate Yankees. We are the ultimate source for biographical and historical information on the Bronx Bombers. Explore the world's most successful franchise ever and dive into the captivating stories of legendary players and iconic moments.

Yankees fans looking for other forms of entertainment particularly those online may like to try their luck playing at an online casino many of which offer baseball theme games.

Test out some great US online casino sites by visiting https://www.bestusacasinosites.com today.

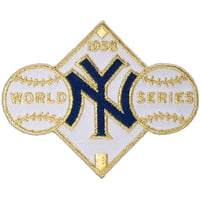

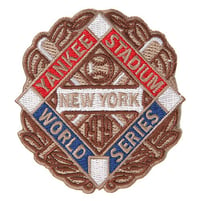

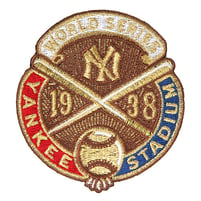

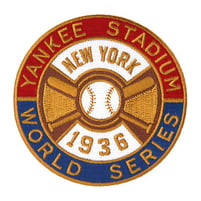

Yankees Patches - Examples from 1936 thru 2009

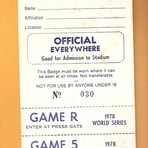

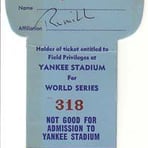

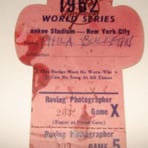

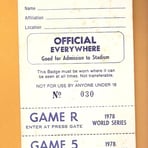

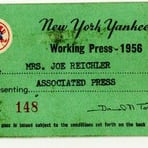

Press Passes from 1956 to 1978